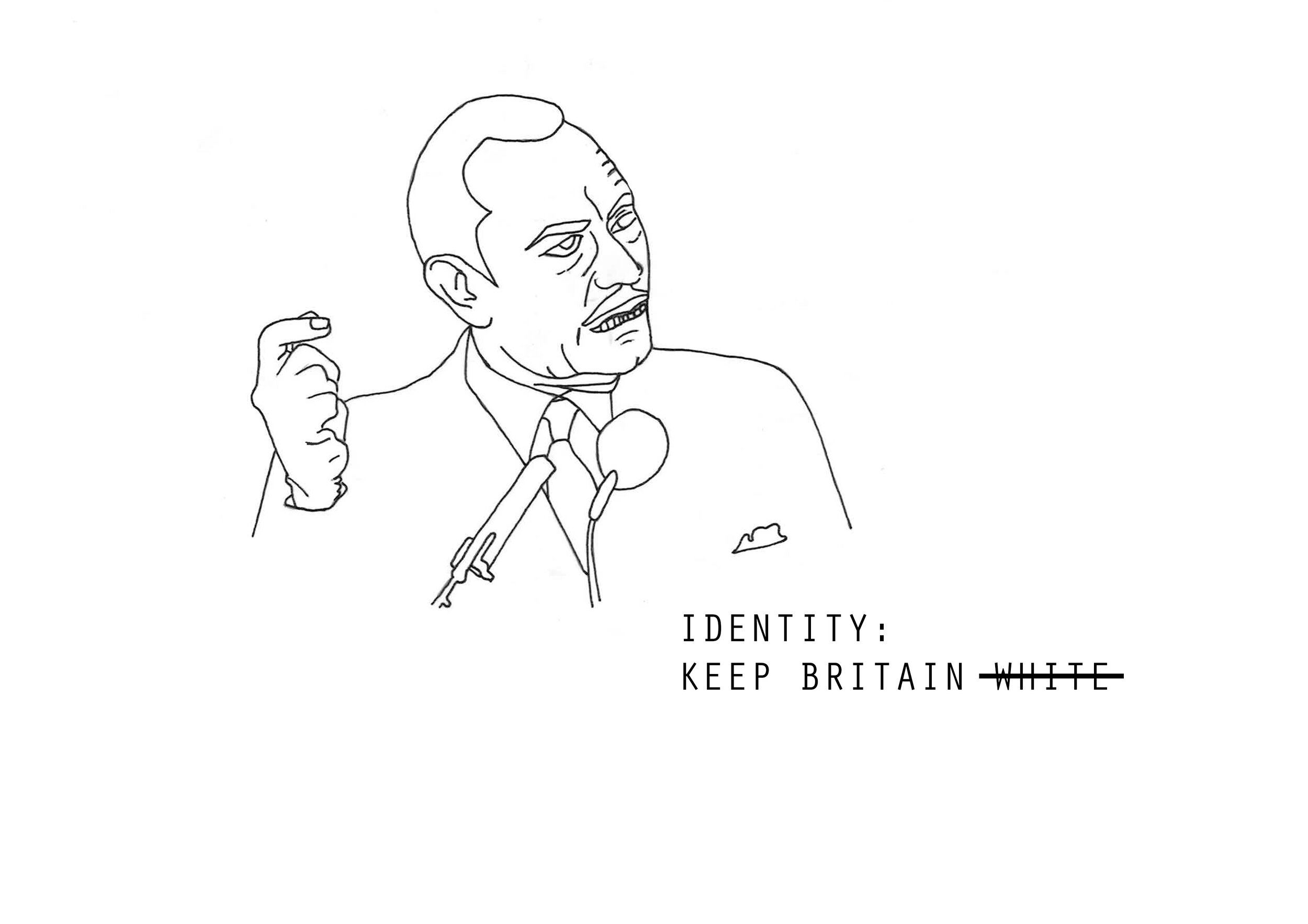

Keep Britain White?

A brief look at my family history in the UK and how it has impacted my work and my complex relationship with identity.

On paper I am British, born and raised, maroon (soon to be blue) passport. I am however black, so of course, I am not native to England. My mother was raised in Jamaica and my father was born in Botswana. Culturally I consider myself to be Jamaican.

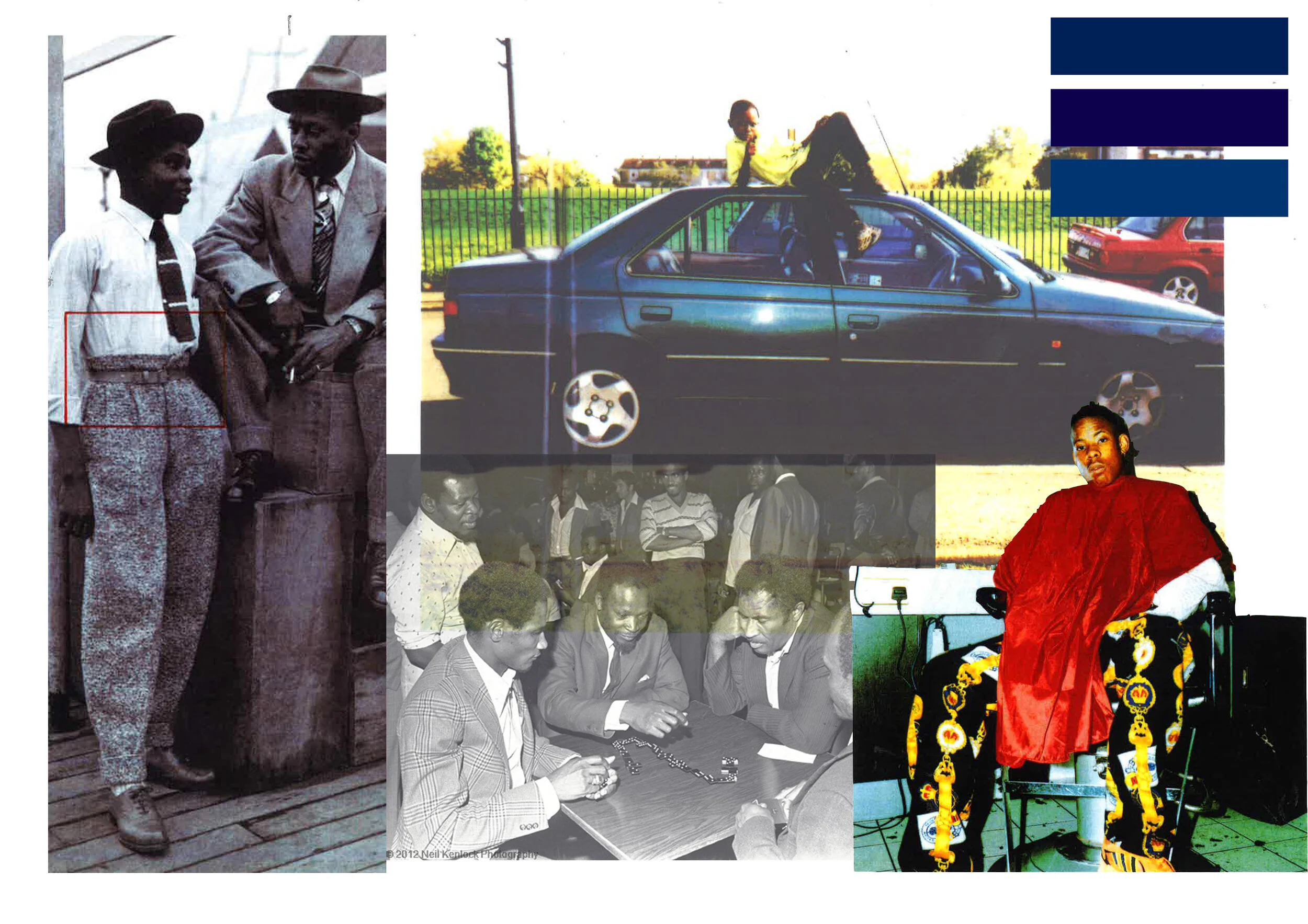

Like many, I was raised in a single parent household. I had an upbringing that many 1st and 2nd generation black British/Caribbean had. The frequent trips to Jamaica, tales of what it was like growing up in the islands, lectures about race and how ‘not everybody is your friend’, questionable décor and ornaments, plastic covered sofas, hybrid roast dinners on a Sunday, the occasional well-deserved beating and the pressure to succeed. It’s a culture I am extremely proud to be a part of.

Growing up, my father denied me the opportunity to understand and be a part of his culture, and now as an adult, it just seems so foreign to me.

Starting out as a designer, my heritage wasn’t really at the forefront of my mind. I wanted to be lauded for my talents, not for my blackness. As a child, my mom would always say that I had to work 10x harder to be as successful than my white counterparts, and that truly bothered me. I wanted my work to show that I am much more than a black woman, I wanted it to show my love for knowledge, history, politics, function etc. That being said, over the years, working within the industry, I have realised that my blackness is something that I can not escape. On many occasions I have been the only person of colour in the office, I have suffered micro and macro aggressions, even been fired because my white managers chose not to try to understand the black vernacular. And for a while, it made me question everything I thought I knew about myself. How can I succeed in the fashion industry if I am not allowed to be myself? What example am I giving to those who will come after me? Am I honouring those who went before me?

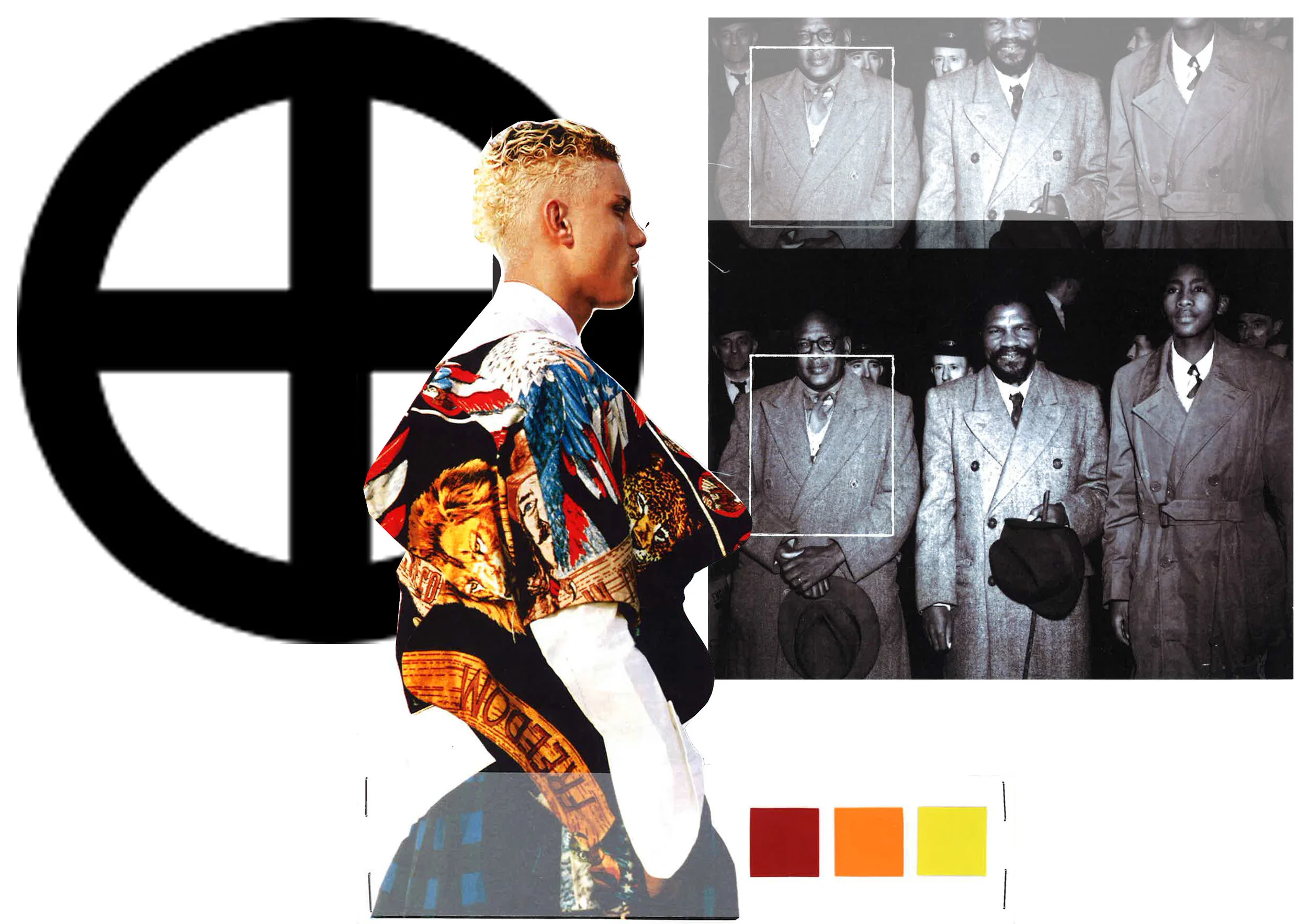

Tomorrow, my collection entitled, “Keep Britain White” will be part of a London Fashion Week digital exhibition hosted by FAD Charity and Fashion Scout. The exhibition, BLM: A Message to the Fashion Industry, is a collection of work by various artists with a message and a story to tell. My contribution is inspired by my Jamaican grandparents, their early years in the UK, the racism they faced, and how things have changed (or not) since then.

In the past year, I have been focusing more on finding my path, and understanding who I am and the impact I want to make. Along with the abhorrent events of earlier this year, and the continuance of racial injustice across the western world, this inspired me to revisit my old collections, and use my grandparents’ story to educate as many people as I can.

My grandparents came to the UK in the 1950s in search of work and better opportunities. Back then, Jamaica was still a British colony and many Jamaicans felt very patriotic towards queen and country. As a result, when the call went out for workers on the islands to come to the UK to boost the economy, many Caribbean’s jumped at the chance. When they arrived, however, the British reception was less than lukewarm. Physical violence, verbal abuse, destruction of property, all were prevalent in their first few years here, and all carried out by their white neighbours. Those that were lucky enough to find jobs and housing were subjected to menial degrading tasks, and squalid living conditions.

They were attacked in the press frequently and used as political pawns. Extreme right-wing groups such as the English Defence League and politician Oswald Moseley, used the large influx of black migrants as an excuse to further their agendas and incite racial violence. Being black was life threatening. At any moment you could be attacked on the street, or denied entry into public spaces, sometimes even killed – and there was very little that the police would do about it.

Despite all of this, the black community stayed graceful and strong in their resolve. No strangers to hard work and suffering, they forged a vibrant community, turning slum like areas such as Brixton and Notting Hill, into sought after locations, gentrified by the hipsters of today. They brought with them their food, music, style, all of which have had a heavy influence on British popular culture. They changed the landscape of the UK, and produced future generations who have gone on to impact the country even more.

My message to the fashion industry? Look at how hard my grandparents worked to make a life here. Look at how much they have contributed. And look at how little has really changed. Our country still has an issue with unconscious bias, and in recent years, racism has been on the rise. In 70 years, we’ve gone from overt racism to covert racism and that is not okay. Black creatives are a minority in the industry, compared to how many of us study creative subjects and pursue a creative career, very few of us end up employed in the industry. Black creatives are more than just tokens. We’re not here to fill diversity quotas or to lead diversity and inclusion workshops. We are talented, we deserve the same opportunities, our voices are valid, and we should be allowed to be our authentic selves.

See more of the collection in the ARCHIVE.