HOMESICK WITHOUT A HOME

On a sunny Friday afternoon in August, 2019, I said my final goodbye to my mother.

I knew it was coming, she had been sick for a while and we had been given warnings, but it still felt like it came out of nowhere. Like it was too soon.

In her death, in one fatal swoop, I lost a parent, but also the world that I knew, the world I had grown up in, and everything and everyone that came with it.

Everything that she had built up around me, crumbled and dissolved. I went from feeling safe and secure to lost and vulnerable. I lost access to her stories, to the people she knew, the connections she had, decades of knowledge, recipes, tools, family history, all the things that shape us, everything that had been passed through the Johnson ancestral line through speech, touch, and smell, never written down or documented in still image.

I thought I knew who I was for all these years, but it turns I knew nothing.

I thought I had more time, I thought in the years to come I could sit down and record the conversations between my mother and I, soak up all the information I needed, learn how to blossom into a true Johnson woman. I thought my family would be immune to the perils of family politics and greed and would lift me up in my time of grief, not fade away.

I just thought I had more time.

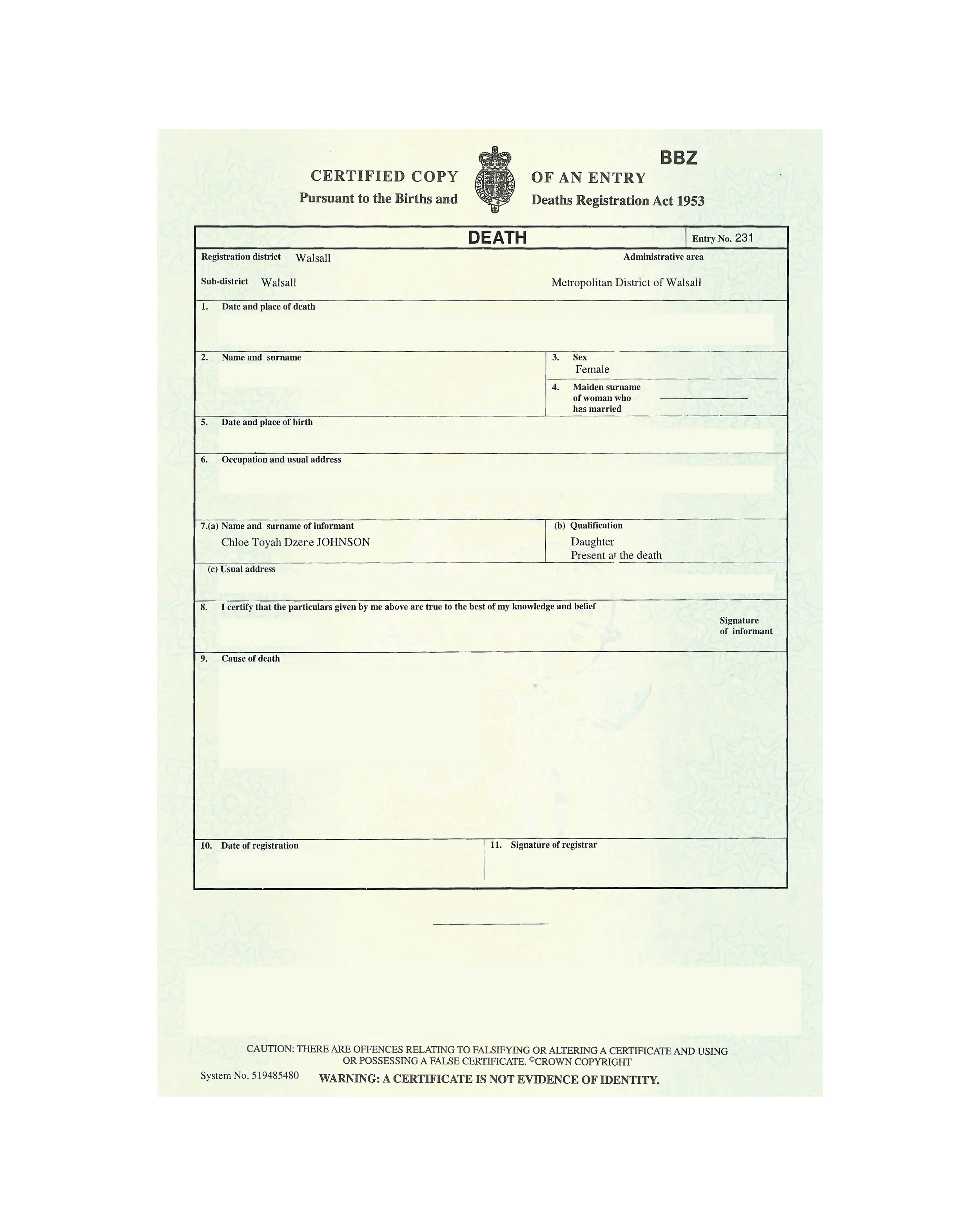

QUALIFICATION, 2022

68cm x 45cm

Digital Print

In my search for healing and connection to my family, I started to look for relatives in the records of the Jamaica Civil Registry - birth, marriages, and deaths from 1880-1999 from parishes across the island indexed and made available to search online. Scouring these archives, I was faced with the disappointment many children of the diaspora are faced with – our family trees can only be traced back three or four generations at most, the further back the search the scarcer the information becomes. From the records I did find, I finally understood the context of many of the stories I had been told, but could also see right before my eyes, the impact of centuries of colonisation on my family and our identity.

Only nine records contain information about my Great-grandma Victoria and her family. I found her marriage certificate, listing the names of her and her husbands fathers - Christopher Halstead and William Johnson. These men are the oldest family members I can find on record, there is no trace of them anywhere else in any of the archives. No record to indicate their places of birth, dates of birth, marriages, or any children or other relatives. All I have is their names.

Beyond this is the ever-present elephant in the room, the thorn in the side, the subject that is often skimmed over in British history books, the events that have led to this lack of information and lack of physical record, not to mention the reason for all these feelings of inherited trauma and collective feeling of loss.

You can’t build a family tree from information that just doesn’t exist. Caribbean families have relied on stories and histories being passed down through the generations for centuries in order to maintain their connection to their ancestry. But after over 400 years of oppression and captivity the original stories become weak and distorted, families get separated, languages are lost, names are forgotten, and memories become vague. As a result, the family history for many begins with the first record of the ‘free man’ and everything before becomes an educated guess.

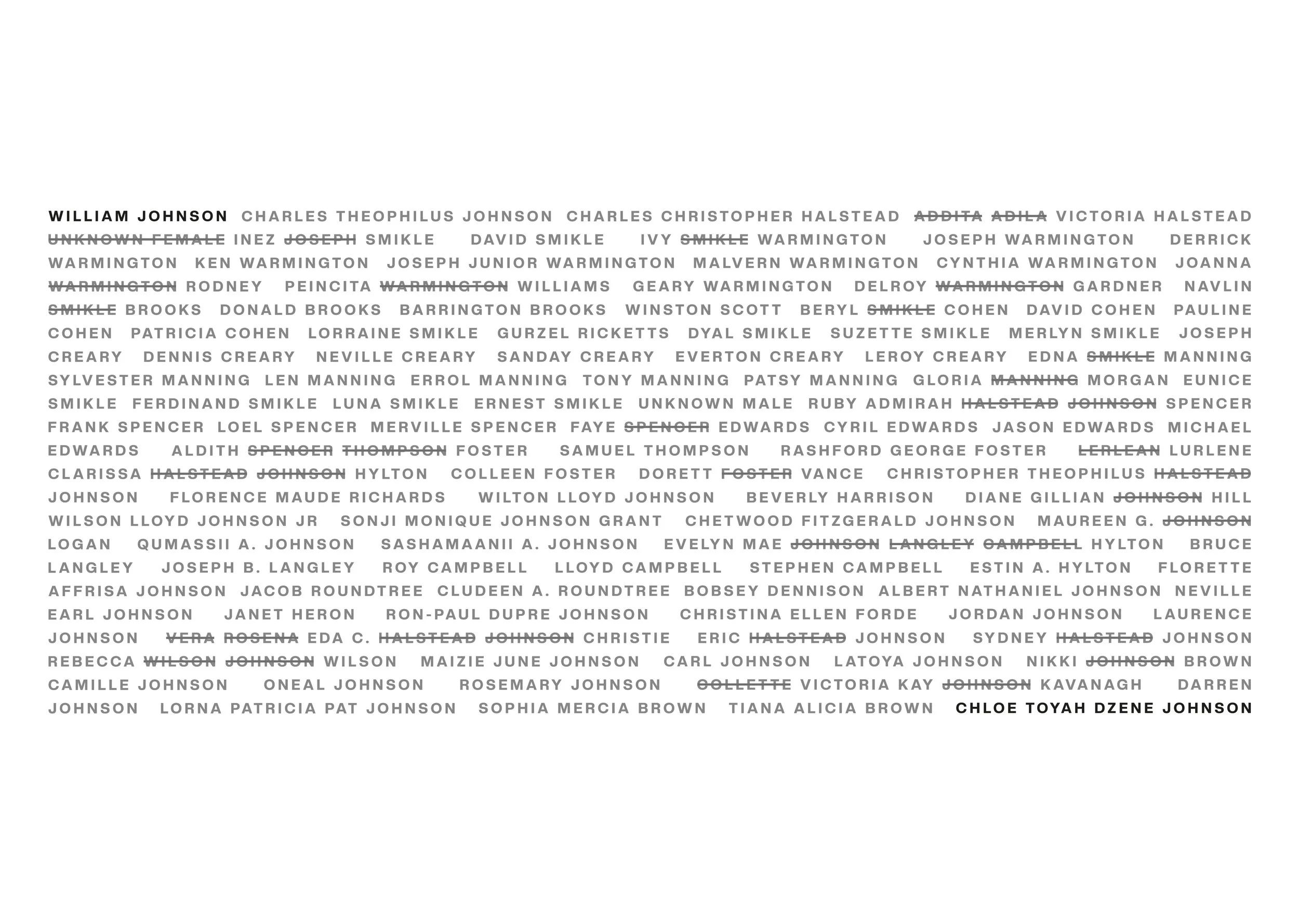

LINEAGE, 2022

30cm x 42cm

Digital Print

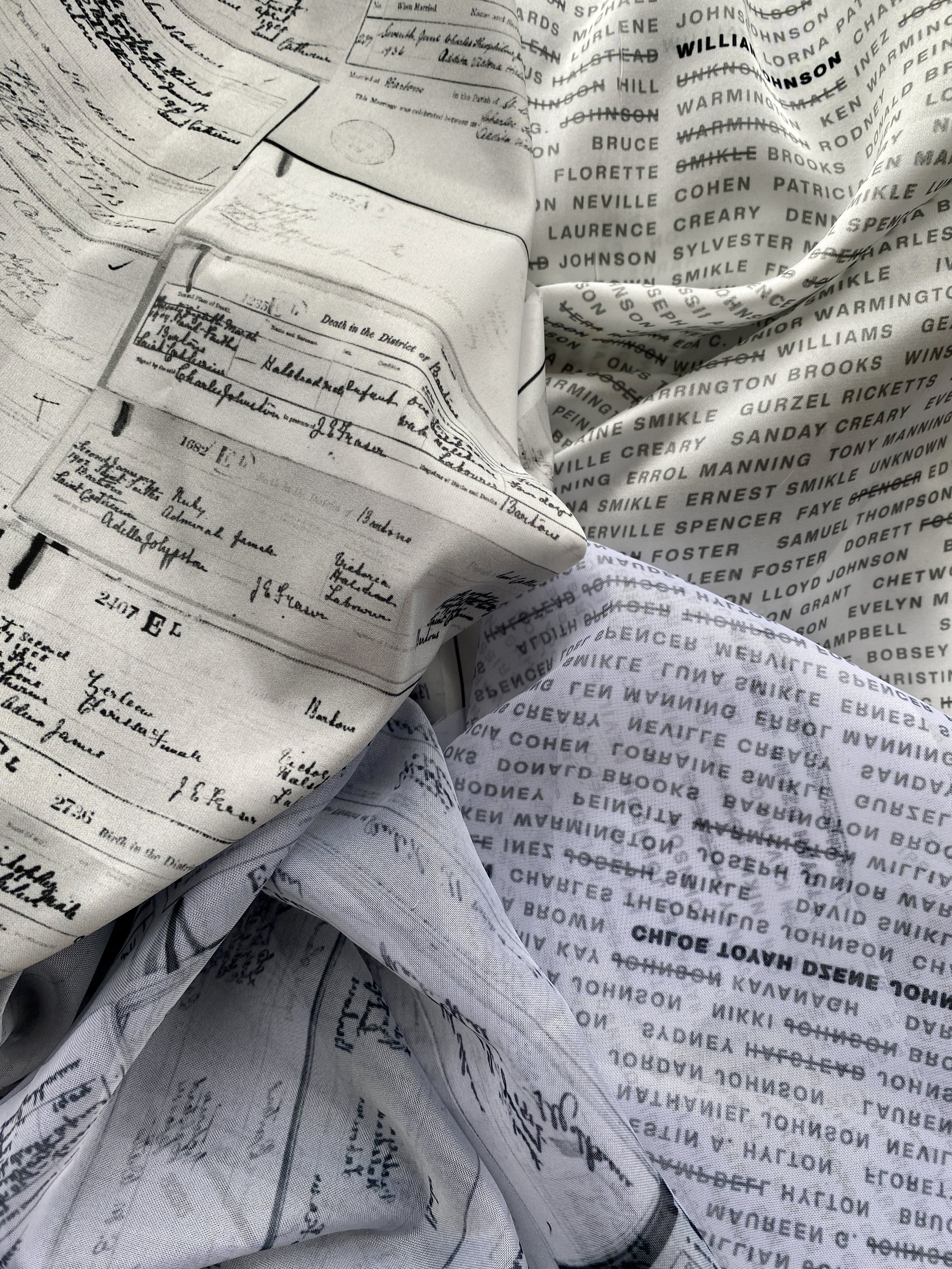

68cm x 45cm

Digital Print on Silk and Satin